Learn More About the Great Blue Heron!

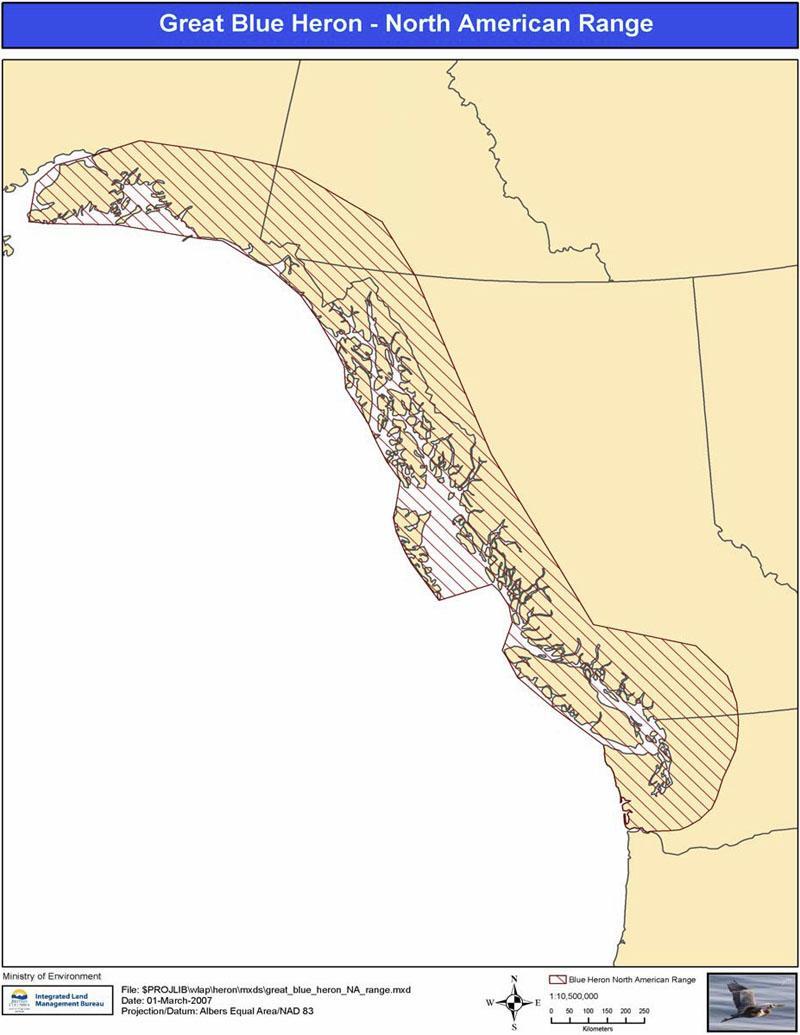

The Great Blue Heron (Ardea herodius) is the largest and most widely distributed heron species in Canada. During the breeding and post-breeding seasons, they venture as far north as Newfoundland and Prince William Sound in Alaska, and as far south as Mexico and the West Indies. Herons leave most of Canada for the winter, with many overwintering across the United States and farther South. The exception to this is British Columbia's coastal areas, where a vulnerable subspecies of the Great Blue Heron (Ardea herodias fannini), also known as the Pacific Great Blue Heron, can be found year-round. The survival of this non-migratory subspecies depends on the presence of suitable foraging and nesting habitat along B.C.'s Southern Coast. They are considered a symbol of wetland conservation and environmental quality by The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada.